| nota

bene! You are looking at an unedited reading script

from a public lecture--it is

NOT

FOR QUOTATION OR ATTRIBUTION.

The

images that appear in this essay are ©2001 W. Nericcio and are not

for reproduction without direct written authorization. The first draft

of this essay was written in 1988--so much has changed in Laredo since

then; so much has remained the same. More recently, a version of this essay appeared as, "Roland Barthes, Mojado, in Brownface: Chisme-laced Snapshots Documenting the Preposterous and Fact-laced Claim That the Postmodern Was Born along the Borders of the Río Grande River, in Performing the US Latina and Latino Borderlands, edited by Arturo J. Aldama, Chela Sandoval, and Peter Garcia, 2012 ISBN: 978-0-253-00295-2 |

| Almost

Like Laredo

A Post-Mortem Cavalcade Laced with Chisme that Purports to Show How Postmodernity Was Born in the Turbid, Fecund Waters Dividing Laredo, Texas, USA, and Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, EUM Modernity, coloniality, the post, and the multiple combinatorial possibilities of these terms have held much of our academic discourse in thrall for some time now...Ultimately, however, our explorations of the issues implied by these terms must countenance the ambiguous question I posit here at a moment we identify as postmodern, in this era we designate as postcolonial: what are we after. --Djelal Kadir Neither will I discuss in any precise detail just what the Postmodern is nor, for that matter, where it came from. Beyond acknowledging it as the latest institutional slot for a new wave of specialists in the Humanities, one knows little of the thing. It seems fruitless to begin here an inquiry into its legitimacy, origin, or hermeneutic. The Postmodern is like Modernism, at least in the terms of our institutional history. Today it is. Someday (soon) it will pass into being was. Should we be living through its death throes, there is still no reason for any disturbance, no need to call in the editorial equivalent of 911 to administer life-saving measures. The death of the postmodern should be viewed for what it is: an employment opportunity. Literary critics retooled as cultural studies pathologists will gather about the corpse to mull over its demise, draw conclusions, and invent its biography--historians, architects and popular culture referees (in the U.S. and abroad) will also have a say. Loading the Instamatic© --Edward Said, 1988 In the humble view of your somewhat biased guide, if you want to survey the epitome of the postmodern city, then Laredo, Texas, U.S.A. and Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas E.U.M are the place to be. As one drives dirt roads on the way to concrete interstate highways, petit bourgeois, Mexican American-piloted imported British Jaguars revving their way past vaquero Mexican American-piloted imported horses (bourgeois, vaquero and horse alike tracing at least part of their ancestry back to Spain), one encounters the bizarre reality of urban/rural entropy on the margins, on the very border, of national, existential and economic legitimacy. What happens to the architecture and the financial and semiotic economy of the urban landscape, what happens to the social relations and cultures of the borderzone’s urbanaut inhabitants when they are divided by and formed through the geographical reality (the Rio Grande/Bravo river) and historically manufactured reality (the peripatetic line separating the U.S. from Mexico) of this site? In order to capture some of this alleged chaos--without totally domesticating it--we will be using pictures to focus on the cultural architecture that has developed amidst two distinct nations and two distinct, if symbiotically determined, border cities. Literary critics and would-be cultural studies aficionados lacking credentials to speak to the complexities of photographs would do well to return to the underrated findings of Susan Sontag to underwrite their course of action. Opening On Photography, Sontag asks what is "the most grandiose result of the photographic enterprise[?]" Her response: it "give[s] us the sense that we can hold the whole world in our heads--as an anthology of images." Sontag’s words here act as augury talismans, warding away the totalizing hubris that might allow us to mometarily imagine the pictures in this essay hold the truth that would give the lie to the prose that cozily surrounds them. For the span of this essay, neither word nor image shall reign sovereign: each reveals the lack of the other. Let us now turn to some recent jottings by Paul Virilio on the ubiquity of the photographic; Virilio writes specifically of war, cinema and culture but more wide-ranging applications are not without some use here: "The problem is . . . no longer so much one of masks and screens, of camouflage designed to hinder long-range targeting; rather, it is a problem of ubiquitousness, of handling simultaneous data in a global but unstable environment where the image (photographic or cinematic) is the most concentrated, but also the most stable, form of information." An opportunistic reading of Virilio’s statement allows us to imagine an encounter with images within the context of an essay where they function as a means to knowing, not as supplements begging for captions but as legitimate, if visual, paragraphs in the strict sense, "lines drawn in the margin," no less a player in the masque of syntax than the commas, periods, and quotations marks that wend there way through this narrative. Barthes’s, Said’s, and Virilio’s assertions positioned as section epigraphs above, emerge as uncanny amulets for our journey, and as keys to this very anthology called The B/order of Things--where a collection of words and images proxy for what might have been called in the past a correct understanding, where an anthology functions as a means to a representation of ontology, a border ontology--or perhaps, better put, to an anthology that negotiates warring versions of ontologies vying for the status of the generic. Something To Say As the Negatives Develop in Lieu of Whistling "The Streets of Laredo" One might preface this tour of Laredo, Texas, and Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas with a return to the term, Postmodern. Let us do so in the form of a dialogue. Assuming the role of antagonist in the following exergue will be Guillermo Nericcio García. William A. Nericcio: There seems to be no doubt about it. Unfortunately most of the criticism using the term is trendy and uninfluential--the more attractive the presentation the less innovative and informing the piece seems. GNG: Is an analysis of Postmodern characteristics a Postmodern analysis in and of itself? WAN: Of course not. An analysis of Postmodern tendencies, practices or theories could be the most clichéd, conservative, reactionary piece/article/section/chapter ever conceived. To be Postmodern there must exist a melange of styles and ideas, even as there must devolve an understanding that said melange is in and of itself suspect--in this regard, the Postmodern is a facile cousin of continental deconstruction, of Poststructuralism. GNG: Has it come to the point that there exist recipes for the Postmodern? WAN: Of course. The Postmodern began somewhere--though where that may be is a controversial subject. We know at least that disciplines like architecture, industrial design, advertising and, perhaps, literary theory, were at its forefront. That one can specify a recipe for such a practice does not endanger its disruptive potential. If anything, it cautions prospective practitioners to enlist some lively skepticism into their practice. Said skepticism allows one to keep one’s practice away from the "Postmodern Cheerleading" that undermines the critical discipline and to move one’s practice towards "Postmodern critical inquiry," which might potentially revitalize literary and theoretical practice by creating heretofore unthinkable interdisciplinary projects. Such revitalizations might change the ivory tower and modify disciplinary traditions. As we move within the new spaces of a third millennia, we are witnessing the changes postmodernity has had on Academe--some of it good, some of it quite awful. Innovation has meant a change in the way critics approach their analyses, prompting some critics to see Postmodern critical practice as pop-historicism in lieu of archival professionalism, allegiance to form rather than the documentation of content, and the valorization of contradiction over that of "simple" understanding. Such conclusions reek of oversimplification and, if anything, unprofessionalism--rank and file reactions to an innovative, if slightly controversial, practice within the critical disciplines. It would be wished that more conservative practitioners within the academy in all the disciplines would seek to investigate Postmodernity rather than ignoring it or running shrieking from it in fear. In this view, one should not fear demolishing the ivory tower. Rather, critics and designers should rush to construct something else in its place. In this new "wooden" tower, perhaps, access to the university would not be based on connections, rank, bank statements, patriarchy, or lineage, but on the willingness of the participants to question continually the boundaries and categorizations intrinsic to academic practices. GNG: Is such a practice possible or feasible? WAN: Of course not--at least not in practical terms. GNG: Why not? WAN: One finds two standard answers:

(1) This is not the best of all possible worlds; and (2) Postmodern practice,

once normed, becomes as repressive as any other bureaucracy. So the key

would seem to be to some sort of rigorous and continuous assailing of all

that has become rigorous. We underwrite change so as to undermine static

method, understanding that this "change" is never essential change but

only some sort of supplementation, to use Derrida’s word, or "shoving"

to be entirely practical. Whether that shoving becomes progressive or not

depends on the goals and desires of its practitioners and bureaucrats.

There is nothing really new or disconcerting about this outlook.

It begins with this bull, the Bordertown bull. Waking up after nineteen years in a small South Texas bordertown--Laredo, Texas, USA, to be exact. Throughout my childhood I thought that the mural featured on the Bordertown Drive-In was of a giant mutant bull, terrorizing the countryside and being attacked by U.S. Air Force jets as a giant cowboy heatedly pursued from behind. I was wrong, of course. That is, I had read it wrong. The giant bull was merely a personal idiosyncratic creation, a misreading, owing to a mistake in perspective. Without the tools to understand the concept of perspective in an illustration, I had taken the mural at face value: giant drawing of bull = giant monster, mutant bull. That the animal was merely foregrounded and thus larger than its surroundings was, at the time, a concept as abstract as quantum mechanics or multilateral arms-control negotiations. The painting was misread. The mural in question faced out on the main strip leading out of and into Laredo and adorned the back side of a projection wall for the local drive-in called the Bordertown Twin Drive-In Theater. Some fifteen years ago, the Bordertown was a booming two-screen haven of movies, alcohol, and sexual abandon for auto aficionados, raucous families, and young adults on both sides of the Rio Grande River. But in the year 1988, that monument was slowly falling apart. No longer a haven for movie-goers, it was home to a flea market open on the weekends, where one could find various used articles, recycled furniture and a huge assortment of deserted, dated consumer artifacts that could have passed as trash in any dumpster. In the half-decade before the current period when the North American Free Trade Agreement and individuals associated with its passage were heralding the arrival of the New World Order, the Bordertown Drive-in was an icon for Laredo itself--a depressed market selling trash in various disguises as merchandise. But then again even trash is not trash in and of itself; trash is not a generic designation (trash for one may be treasure to another). Given the depleted economic resources of the city, even trash might be repackaged in some way so as serve a purpose or garnish a profit. Even the Drive-In had been repackaged as a pulga, as a flea market But let us not allow the caress of nostalgia to blind us from the present for I must report that the Bordertown Drive-In/pulga is no more. The Godzilla-esque bull has been erased from the space of Laredo--my photograph must proxy for the structure as a kind of ersatz visual relic. The structure was torn town and sold to the Wal-Mart corporation. On the site of the giant cow arose the specter of what is known as Sam’s Warehouse--a discount marketer of groceries and other assorted sundries. Gross sales of Laredo’s Sam’s Warehouse and Wal-Mart were so huge that just before his death in 1992, Sam Walton flew to Laredo to celebrate his profits. Walton was visibly weak and ailing as he greeted cheering workers and shoppers like some latter-day vision of Cortez. I would have included a picture of the store if I didn’t miss that old bull so much. A Disclaimer as the Author Mourns the Loss of a Precious Bovine This section, as one will have noticed already, represents less a cohesive analysis than a leisurely tour--a pictorial travelogue or post-colonial safari. Some will view such an approach as critical eclecticism. So be it. As Stuart Durant concludes, "eclectics have never been strong on theory. Eclecticism seems essentially the mode of practitioners." Though Durant speaks here of collectors of furniture and their tastes, he may have struck upon something useful to would-be theorists of Postmodernity: one may have to focus, like it or not, on either theory or practice in order to accomplish anything with one or the other--one must select a fetish and stay with it lest the fetish devolve into a dalliance, a whim. If this travelogue adds nothing to the current debate in Postmodern theory, it would at the very least like to be considered a bastard example of Postmodern critical practice--bastard in that it feigns no interest in and makes no claim to legitimacy in any way, shape, form, or species. This approach asks much of its readers/spectators/tourists: that they suspend common, even enlightened, understandings of Postmodern design and architecture; that they consider how intriguing architectural fracture and cultural production go on outside the metropoles, those cities that represent the headliners, the core, the cream of the crop, the advance guards of capital, production, and consumer innovation. But what of the backroads? What of the border? If one isolates a core, one must also have a periphery to isolate that otherwise abstract center. Enter Laredo. As bizarre a periphery as any

one is to find in the global safari one calls urban criticism, architectural

inquiry, or textual analysis. Laredo is eccentric; it is, to signal this

author’s debt to Canadian theorist Linda Hutcheon, "ex/centric": both outside

and inside, in short, deliciously and uniquely marginal.

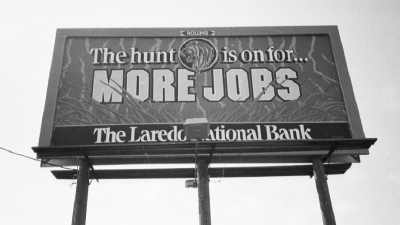

The Second Frame, Where The Hunt Is On for More Jobs

The economies of these sister cities are bound intimately to each other. When currency values plunge so goes the fate of the two cities. So while United States tourists reap the rewards of cheap Corona beers and ridiculously underpriced Mexican leather goods, Laredo, Texas, USA, downtown merchants shake their collective heads and wonder where the business went. Recall here that the eighties was the decade when oil-price futures went bust in Texas and that South Texas, Laredo included, is one of the richest oil and gas regions in the fifty states. Now one begins really to understand why "the hunt is on for more jobs" in Laredo. These savage and elusive beasts are just too scarce for the standard safari, so Laredo’s largest financial institution, The Laredo National Bank, has come in on the project as sponsor of this semiotically disturbing series of billboards and TV commercials (television spots featured footage of ferocious lions roaming green, dangerous jungles and grass strewn plains). The lion, incidentally(?), is the trademarked icon of the Laredo National Bank. Do you hunt the lion? Or does the lion hunt you? LNB’s latest semiotic enterprise,

their online banking service illustrates that when it comes to transnational

Capital, banks on the border must speak at least two languages: dollars

and pesos, English and Spanish, Washington and Juarez.

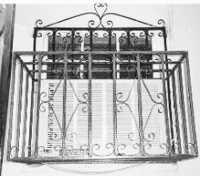

The Third Frame, Wherein It is Shown that Even Appliances Have Cages on this Safari

And what beast do we have here? While the photo in question might be a representative offering from a MOMA exhibition in New York or MOCA exhibit in Los Angeles, that it comes from a backyard in Laredo, Texas, is entirely significant. The result of the scarcity of jobs in Laredo, Texas, is a numbing increase in the crime rate in the city, particularly burglary and armed robbery. In times of economic despair and growing unemployment, one either sucks up one’s gut, tightens one’s belt, joins a job safari or deals drugs and steals. Hence, the air conditioner in the photograph has been placed in a cage of black wrought iron to help guarantee it will stay in place--without benefit of its protective wrapper, it might have ended up at the old Bordertown pulga. Even at the height of the economic bust of the mid-eighties in Texas, Laredo had a larger number of prospering banking and saving institutions than many other cities in the Lone Star state. Then again, perhaps this is not as surprising as one might think at first. The DEA has shut down much of the Miami cocaine connection, but Latin American drug barons continue to move with relative freedom through Mexico. With one avenue of distribution cut off, the drug-mules have turned more and more to South Texas and Southern California to export these tasty narcotic goodies. The profits from these transactions don’t end up usually in the proverbial grimy bus-station locker. In fact, with growing frequency, drug captains are turning to legitimate financial institutions to shelter their wealth. One has a better idea now of exactly whose money finances part of the Laredo National Bank’s "hunt for new jobs" in Laredo. For the rest of Laredo, though,

belt-tightening is the only recourse. With 117ûF temperatures during

Laredo’s summers, air conditioners are as valuable as water in the desert,

and the best one can do is encage the house and hope for the best. The

air-conditioner in a cage may well serve as an icon of Laredo’s periodic

economic crises, trapped as it is behind the bars of economic inertia.

On this safari we’ve reached what may well be a point of despair--Laredo’s

two icons are a flea market recycling yesterday’s refuse and an appliance

ensconced in a black iron cage.

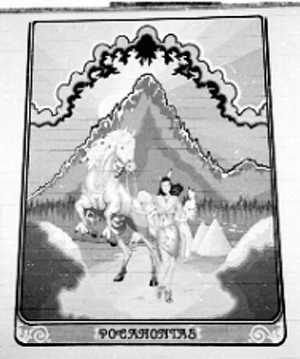

The Fourth Frame, Wherein George Washington Meets Pocahontas and Has a Peculiar Fiesta in Laredo A total of seven flags have flown at one time or another over the lands presently designated Laredo, Texas, USA. This has led, as one might imagine, to a bit of schizophrenia, loosely speaking, in the cultural identity of the community and in its celebrations, which are, after all, the best reflection of the complexion of a community. If one is what one eats, then it might just as easily be said that a city is what it celebrates. How decidedly strange and "postmodernesque," then, that Laredo’s largest celebration each year is The George Washington Birthday celebration. Apparently started by a group of nostalgic Anglos and outsiders living in Laredo after the turn of the last century, the celebration continues to prosper in Laredo’s largely Mexican American community. Each year the haves and the have-nots line the famous streets of Laredo for a week-long celebration that includes a colonial ball(!), debutantes, parades, cook-outs, and a carnival; also, said extravaganza includes Pocahontas. It taxes the imagination to wonder how a celebration of the United States of America’s first president and noted slave-owner, George Washington, ever got caught up in a beauty/popularity contest for the role of Pocahontas in the annual George Washington’s Birthday Parade--an award whose chief distinction is parading on horseback for the better part of a morning. One imagines the founding fathers (of the yearly celebration, not of the country) thought that since both Pocahontas and George Washington could be found within a certain number of pages in a high-school history book, why not link the two together--or something like that. In any event, every year during the celebration one lucky (popular and politically well-placed) young woman gets to don a leather outfit and become Pocahontas, riding her decorated horse up and down Laredo’s avenues with marching bands in front and festive floats and street sweepers bringing up the rear. Let us move to the snapshot in

question. Pocahontas, horse, mountains, sky and all, adorns the front wall--a

mural commemorating the yearly ritual--beside a money-exchange house where

tourists may, ala MacDonalds, drive up and exchange there dollars for pesos

at the latest going rate before driving across the Juarez-Lincoln International

Bridge. The conflation of murals, Pocahontas, money-exchange, George Washington,

and debutantes provides a succinct example of the narrative/festival pastiche

riturals informing the matrices of Laredo.

The Fifth Frame,

Wherein It Is Announced, and Not For The First Time In Hermeneutic History,

That Celebrities Are Commodities

Why dally here with a billboard?

Both ideological citations and changeable urban tattoos, Billboards reflect

like giant mirrors the taste of the urb they decorate, and, like mirrors,

also affect the tastes, appearance, and actions of the individuals and

communities who gaze at their reflection. Top bill performers, sharing

the stage with buildings, monuments, murals and historical sites, billboards

are beasts central to this safari.

The place? Laredo, Texas. The object captured by the photographer? An African American groomsman

statuette/hitching post stands behind a standard cyclone fence. A provocative

common piece of Americana, an outdoor-furniture design peculiarity, as

well as a pertinent historical artifact that speaks to a particularly "American"

form of racism, here the mute servant marks the modest domestic habitat

of a lower middle-class Mexican American family--unlikely to have slaves,

grooms, let alone horses milling about their 1 1/2-car outdoor garage.

Demographically as well as geographically, the statuette is out of place

here in the borderlands of the South Texas/Mexican border. Not that one

could not imagine a context where said statuette might be appropriate.

Surely Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’s foyer cries out for such

a monument?

On the left of this picture is Los Estados Unidos de Mexico. On the right rests the United States of America. In the middle (see speck) floats a Mexican national in an inner tube, rafting his way down the middle of the Rio Grande river, which, incidentally, is called el Río Bravo by Mexicans who reside on the left side of this picture. This image renders the split that produces the heterogeneous peoples found on both sides of the river. This is where it all happens: in history (border clashes and raids by armies and bandits from both sides of the river); in the present (drug smuggling, illegal immigration, illegal sewage and radioactive toxic-waste dumping on both sides of the river. The explosion of maquiladoras--multinational owned and operated factories producing goods for export on Mexican soil--has accelerated this dumpage. A few minutes after this picture was taken, the subject in question, dressed only in underwear with a bundle of clothing in his lap, floated under and past the bridge I was standing on, shouting obscenities and choice epithets to friends and spectators along the railing of the bridge. The last I saw of him, he was docking his craft and scurrying intently up the banks on the U.S. side of the river. Never before had the self-importance of an international boundary line seemed so insignificant; never before had the autonomy of two nations seemed so arbitrary and capricious. Never before, that is, until one minute later, when horse-riding, gun-toting officials from the U.S. Border Patrol came up and apprehended our aquatic boundary challenger. What began as a significant displacement

of the now-not-so-abstract borderline, became an everyday, legally determined,

and quite common international incident. One expects the boundary crosser

will return at some point to the U.S., probably more sooner than later

as standard procedure in these cases is simple deportation--a handcuffed

two-minute walk across the International Bridge back to Mexico, freedom,

and, perhaps, more inner tubes.

The cropped portion of the boundary marker reads "one for all and all for one" like a line out of a Three Musketeers movie--and given the cinematically determined reality of the United States during the Reagan administration (movie star/president, Star Wars the movie and Star Wars, the Pentagon weapons initiative, etc.), such a cooincidence is not altogether surprising. Below this slogan are the important words: "Boundary of the United States" and "Límite de la República Mexicana" established in 1848 and "re-established by the treaties of 1884-1889." This really is the borderline, the margin, the end of the frame, the inside/outside boundary, the point where self and other differentiate their particular identities--this is no metaphor, just ask the floating speck in the last frame. Alternatively, one can see the border as the site that licenses all metaphorics--the border as autochthonous agent for all concepts communicating difference, metaphors included. In any event, this boundary marks

one of the many spaces where the United States of America and Los Estados

Unidos de México both begin and end. But in an age of Postmodern

sensitivities, we should be in tune with the fact that such an absolute

binary must be taken with a healthy dose of skepticism. It is interesting

to note that as one looks in either direction, on either side of that boundary

marker, an ongoing process of salacious willed and unconscious intercontamination

prospers on both sides of the line.

Some are more innovative than others. All of us have met them in one form or another--some of us have been them. They range in name from street performer to pan-handling bum. What they have in common are the streets, passing strangers, and fear of the authorities, whoever they might be. Here, in this photograph taken in Nuevo Laredo, the dancer wears vestments akin to those sported by Mexica warriors at the height of their imperial reign some five hundred years ago. He has, however, exited the frame of that period (traditional vestments become mere costumes once outside their particular ideological context) and entered a very different cultural enclosure. The street performer’s dancing and chanting patterns derive from the theocratic, polytheistic ritual of one of the indigenous peoples of Mexico. Here, the ritual has been translated from one of political and theological (theocratic) significance into one of mainly economic significance--he’s dancing for money. One moves from the interpretive economy of theocultural rite to to the interpretive economy of the soliciting spectacle, the economy of the unique, individual act. In addition, the dancer enters here, also, the very literal camera frame of the safarist/analyst photographer and the critical frame of our ontology/anthology. He has been translated once again--and

unwillingly (the dancer in question turned to avoid the camera several

times forcing me to slip inconspicuously across the street to seize [t]his

image away from him). He is now more than just a performer earning his

keep; he now becomes an interpretable image/text, an alienated object.

When Sontag notes that the "photographer is not simply the person who records

the past but the one who invents it (67)," she reveals the determining

and objectifying logic of photography. The dancer has become a suspended

iconic signifier begging for description in the antiseptic pages of an

academically sanctioned intellectual safari.

The Tenth Frame, Which Documents the Chance Rendezvous of Spain’s Don Quixote, Aztlán’s Quetzalcóatl, and England’s Ozzy Osbourne Walking down Nuevo Laredo’s main street, La Guerrero, down a few blocks from the International Bridge, one finds a beautiful plaza--a park with trees, swing sets, shoe-shine stands, and running children. In the center of this park stands a small library with a beautifully detailed mural gracing its front entrance wall. The mural depicts Don Quixote atop his steed charging toward Quetzalcóatl, a Mexica deity. The mural in question does not depict a scene from the text of Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quijote de la Mancha. Rather, the unsigned mural renders the complex fusion of European Spanish literature and culture and indigenous Mexican literature and culture. In it, specatators’s eyes witness the condensation of elements from two sixteenth-century avatars, one Spanish and one Aztec, into the medium of the public mural. Epic figures from mythology and literature are given to our eyes as pictures. In the middle of Nuevo Laredo a story from Spain meets a story from Mexico and both find translation in an instant upon the wall of a public library--note how the mural shows both figures rising out of the pages of texts, the European printed and bound book and the Aztec printed codices. Textual denizens here become agents in the domain of pictures, and the photograph of this image immediately becomes analytic property--a semiotic artifact. But there is more here than initially meets the eye. Our tenth frame illustrates a troublesome semiotic development as a Postmodern anomaly interrupts our analytical progress. Someone has intercepted this mural. Someone has re-signed this mural and displaced further the already complicated semiotic overdetermination of the original mural combining as it does the literary and cultural peculiarities of two disparate tribes, Euro-Spanish and Pre-Columbian Mexican. Look again at the picture. Down toward the bottom of the mural and across the pages of the Aztec codices and Cervantes’ book lurks the following readable autograph: "ozzys Boys." Just who are these, "ozzys Boys?" Ozzy Osbourne, late of "Black Sabbath" and currently a solo rock performer, is a somewhat popular English "heavy metal" rock star. Aside from a few scattered hits and appearances on MTV, he is known mainly for biting the heads off live bats in concert to the delight of his adoring fans, one of whom, it is apparent scrawl edhis graffiti autograph upon the scene of this mural. Interception. Ozzy meets Quixote meets Quetzalcóatl. That the already complex depiction of a meeting between Mexico and Spain, with all its imperialistic and exploitative history, has been further complicated by a British autograph from a Mexican-American hand leaves one with little if anything to add. More words would only distract from the already eloquent testimony of the photograph. Sometimes, the caption must shut-up.

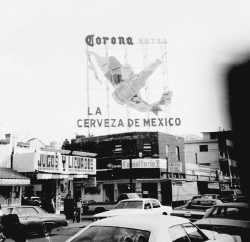

Walking down the Guerrero, just

past the intriguing signature of "ozzys Boys," we find a monument worthy

of Mexico’s rich history, a lighted, extravagant billboard extolling one

of the champions of Mexico’s export economy. "Corona, La Cerveza de

Mexico/Mexico’s beer," the sign bellows out for all to see. While the

message will be familiar to Unitedstatesians daily bombarded with beer

advertisements, it is the image itself that is most striking in this instance--a

detailed and geographically accurate rendition of Los Estados Unidos de

Mexico with a huge bottle of Corona Beer splashed across and jutting out

from it at a provocative angle. One might, if one wished, dissolve the

descriptive frame at this point and begin a Derridean, Lacanian, Freudian,

or Bergerian analysis of this lovely montage and document the overdetermined

iteration potential of this image, or one could, à la Barthes, wittily

pinpoint the connections between the image and the culture of the natives

daily whizzing past it only unconsciously conscious of the display’s influence.

One might, also, assume a Marxist bent and read this giant ad as an allegory

chronicling the incredible growth of Corona beer sales in North America.

Rather than explore these trails, this safari’s listless docent would,

instead, enjoy asking the following question: is nationalism (the prehistoric

grandfather of what marketers called branding) becoming implicitly the

most marketable means of expanding market share in the current period?

Still on the Guerrero, one comes across Sánchez Funeral Home, a necessary if depressing commercial enterprise situated on the main business strip. It is a sad, drab outlet situated beneath a small apartment complex. The striking feature here is the live palm tree growing up through the first floor and out the ceiling of the second floor balcony. From the first time I saw it, I did not doubt what I saw. There are some places where one never doubts what one sees--Las Vegas is one, the South Bronx another, and Nuevo Laredo yet another. This was more than just another

visual oddity, though. The mating of human and natural architecture was

charming--as if the two architectures, not wanting to offend each other

and yet strapped in the way of space, had decided "what the hell" and taken

up residence on the same plot of land. Here again, travelogue spectators

and ideational safari enthusiasts are presented with much in the way of

semantic/semiotic conjecture--life meets death, tree meets mortuary. In

a symbiosis almost too rich for the inhabitants of an increasingly homogenized

reality to comprehend, one is immediately confronted with the seductive

contradiction of life breaking boundaries (the palm tree), versus the mundane

bureaucratic reality of death (local funeral laws in Mexico mandate the

internment of bodies within a twenty-four-hour period). Postmodernity cannot

claim the rights to such a sight--it was there and growing before Derrida

ever sent a post-card. It would be all right to contend, though, that a

dutiful worship of this semiotic tableau embodies a signature ritual within

the canon of Postmodern practice.

So I go back to Nuevo Laredo some ten years almost to the day after I took my first photographic safari and I see it . I see it in all its allegorical potential--the tree for me that symbolized the domain of the ironic, the Sánchez Funeral Home that for me embodied all I understood about the unsettled and turbulent, not to mention comedic, dynamics of the Mexico/U.S. borderlands had been altered. Some clumsy, unlicensed, would-be tree surgeon had, in the effort of trimming this public, natural "sign," killed the damned thing. Uncanny, how things change, how

the years fly by. Still uncannier, a van with a roof ladder figures prominently

in the right margin of two photographs divided by a decade of life and

chaos.

No other site on both sides of the river gathers more tourists than the Cadillac Bar and Restaurant pictured here in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. "The Cadillac," as it is affectionately nicknamed, serves also as a haven for alcohol-starved teenagers from Laredo and Nuevo Laredo (the drinking age in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas varies in ways that recall the logic of roulette wheels). Thirsty tourists out for a good time or a rest (Nuevo Laredo is well known for its treacherous streets and sidewalks), Mexican nationals stopping in for a quick lunch or dinner, and businessmen and women from both sides of the river talking finances over a Ramos Gin Fizz©, all make their way through this tavern’s history-rich double doors. Waiters bustle about in their prim white jackets, tight black slacks, and audacious ties serving tough steaks and warm nachos to their boisterous audience. At night and on weekends, diners and drinkers find themselves treated to the piano-accompanied singing of Mexican and United States musical standards by strong-throated Mexican crooners. The Cadillac favorite is "New York, New York," a song guaranteed to lift the spirits and delight the senses of tourists from all over the fifty states. This watering hole certainly enhances the cultural topography of the sister cities, Laredo and Nuevo Laredo. When aging tourists from the American Midwest make their way through here with their circa WWII song requests, it is as if Glenn Miller never died, Hope and Crosby were still a team, and Ronald Reagan was a harmless, affable, if insufferable, B movie actor. Sitting around, downing a Dos Equis cervesa and surveying the local and visiting wildlife one night, I was struck by the youth and abandon of the mingling throngs. Young Laredo Catholic-school girls, some barely fourteen, sauntered and swayed about in fashions out of Elle or Vogue, cigarette and drink dangling from each hand. Young boys, dark or blond, moussed and arrayed in the latest fashions by Ralph Lauren, Perry Ellis, or Giorgio Armani, accompanied the young ladies, all partying gloriously to the strains of "New York, New York" while patient waiters assisted them with their every wish and need. In Laredo, Texas, (on "the other side" of the river) meanwhile, the have-nots or the unlucky were cruising up and down Malinche Avenue trying to buy beer at some convenience store down the way (that is if they were lucky or had an older sibling). As a result of the vagaries of alcohol procurement, Laredo high-school students, college-goers and other assorted fun-seekers spend most of their hours on the Mexican side of the border where the favorable dollar/peso exchange rate and unpredictable law enforcement create an urban night life as alive, innovative, and dangerous as any other in Toronto, New York City, or Milan. For 25¢ cents one crosses a turnstile and enters a heterogeneous oasis where all things good and bad are possible. Crossing that line, Laredoans enters another world. Almost a Conclusion: A Border Culture Primer Laredo has a little bit of everything. More international goods pass over its bridges than at any other inland port in the nation. As such, many nationalities find themselves represented here. For the most part, though, the community is Mexican-American. This being a semiotic enterprise, the term "Mexican-American" is as good a place as any to bring this safari to a close. You will remember the International Bridge referred to earlier. It would not be far from the truth to suggest that Mexican-Americans carry a graphic signifier of that bridge wherever they write their collective autograph, wherever the word Mexican-American or Mexican American is written, spoken, or acknowledged. Mexican [-] American Estados Unidos de Mexico [-] United States of America How much imagination does one need to see that hyphen as a bridge? The fracture of subjectivity (the alienation) thus depicted, one might think that a further exploration of alienation, anomie, or cultural schizophrenia might be in order. Unfortunately, the demands of this almost denouement do not allow for it. One could propose, in contrast to that view, that the hyphenated interaction of these two rich cultures across that bridge creates the generative space from which the semiotically rich contradictions of bordertown culture are born. Determined by their proximity to each other, Laredo, Texas, U.S.A. and Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, EUM continue to manufacture their own brand of Postmodern urban reality. While many would perhaps rest content to catalogue the depressing alienation of such an economically malaised and culturally marginal pair of communities, it seems just as valid to view them otherwise: as representative contiguous constellations enacting subversive metastrophic exchanges that produce continually new versions of their contradicting and derivative identities. In the end, Laredo and Nuevo Laredo

are not representative of the Postmodern moment. They are where it was

born.

The final shapshot I will show you is a shop sign in Tijuana, Mexico where the word "Aztec" appears in Japanese. I think it provides a fitting final allegory for the borderlands as we enter the third millennium--Pacific Rim multinationals lacing the U.S./Mexico borderlands with both language and Capital. The shop sign makes it all that more difficult to imagine borders as simple lines dividing, hence shaping, two entities. There are always more than two players afoot, and the transnational semiotic Babel provided us by this Northern Baja California emporium disabuses us from our old habit of relying upon thoroughly logical and utterly misrepresentative binaries. With the changes exploding across the boundaries of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in recent years, many of the self-evident notions about the order of things have been blown out of the water. It is not just the union of associated mapmakers in, say, the former Soviet Union or Germany who will profit from these metastrophes--these changes in the name and constitution of various political and national bodies. Border theorists are having a ball--those of us who pontificate and prognosticate on the dynamics of border interaction can also gain much from a careful scrutiny of this late twentieth-century happening: border checkpoints come, border checkpoints go as the Berlin Wall comes down and Checkpoint Charlie files for unemployment insurance; meanwhile, the United States militarizes its Mexican border, soldiers in camouflage supervising as a new iron curtain springs up, forged from unused metal instant runway sheets used in the Persian Gulf War. Elsewhere in another isolated border precinct, a Cuban American U.S. Marine screams with glee as his Pentagon-issued carbine rips the life from a nefarious drug smuggler--that this agent of narcotic malfeasance is an innocent U. S. teenage, herding his family’s goats, well, that’s....well that’s just the price we pay for freedom blah blah blah blah blah... So as the walls come tumbling down, with or without the melodrama of Jericho, other new structures are going up in their place. Theses barriers, much like the carbon-based organisms that erect them, are always evolving. One of the tasks for those of us curious about the Border is to document the latest line of barrier fashion, the latest trends in border checkpoint accessories--drug-sniffing dogs, moonlighting Special Forces troops, pilotless reconnaissance aircraft etc. This fetid interlude of reverie has led me to think through the impact of Late Capital and the advance of a global multinational economic New World Order on the site called the border and to the writings of Karl Marx. It is not without a certain bit of nostalgia that I have returned in recent days to a patient if haphazard reading of Das Kapital. With the championed victory of Capital, the introduction of a corporate culture industry to Eastern Europe (and who wouldn’t want to trade in their scowling politburo chieftain for a smiling, young, and nubile Ukrainian simulacrum of Vanna White), with all this it seems worth the effort to re-survey the pages of a startling writer who the masses seem to regard as passé or, worse yet, a fool. There in those pages, working through the chapter on the production of relative surplus value, reading through the section on "The Division of Labor in Manufacture, The Division of Labor in Society," I stumbled across Marx’s extended quotation from the writings of a British Lieutenant Colonel/Orientalist/anthropologist stationed in India--thankfully, Edward Said has made it damn near impossible for us to forget the subtle links tying the repressive state apparatus of the militia to the social scientist and the university. Anyway, here Lieutenant Colonel Mark Wilks in Historical Sketches of the South of India, 1810-1817 describes the peculiar economy of a small communal socius. Marx via Wilks notes various activities doled out among the member of what he calls a "self-sufficing asiatic society." These "boundary man" inspired-thoughts did not end there. I called to mind the self-rightous bogey men of the intellectual conservative Right, boundary men like William Bennett, Irving Howe, E.D. Hirsch, and Allan Bloom--and their peculiar neo-Fascist bedfellow, Pat Buchanan--guardians and cultivators of a facile and ideal cultural inheritance. At the same time, my mind drifted to the Left, to those of us who think ourselves specialists not of "guarding intellectual borders"--but of studying them, which if we follow Deleuze/Guattari means much the same thing. Even those of us who understand frontiers as geological/national/social sites of conflict--where binaries like self/other, subject/object, and citizen/alien find their most eloquent deterritorialization--can fall prey to the ontology of the boundary man. The more naive of us who propose no boundaries at all are merely the more sophisticated in their dissimulation. I mean to speak frankly. I’ll take the checkpoint in lieu of internalized colonization any day of the week. If bordercultural studies are the latest rage and pundits on the right and the left sing the praises of some utopian construct named multiculturalism, the fractiousness of border regions whereever they may be will continue. The subtle and overt subterfuge of the border is beyond total containment. We should worship its diastrophic rumblings without which there would be no Subject to deconstruct, no subject to speak of. Almost like Laredo. I almost like Laredo. I am almost like Laredo. Amidst these three phrases lurks a version of the two of us: you and me. |

William

Anthony Nericcio, born in 1961 at Mercy Hospital, Laredo, Texas, is

Professor of English and Comparative Literature at San Diego State

University.  A 1980 graduate of St. Augustine High School (Go Knights!)

in the Heights, he graduated with a degree in English from the

University of Texas at Austin in 1984 and completed his MA (1987) and

PhD (1989) in Comparative Literature at Cornell University. Nericcio is

the author of Tex[t]-Mex: Seductive Hallucination of the "Mexican" in

America. In August 2009, Nericcio began his new post as Director of the Master of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. A companion piece to this essay sobre Laredo appears in SDSU PRESS's Border Lives (1995); a selection appears here. A 1980 graduate of St. Augustine High School (Go Knights!)

in the Heights, he graduated with a degree in English from the

University of Texas at Austin in 1984 and completed his MA (1987) and

PhD (1989) in Comparative Literature at Cornell University. Nericcio is

the author of Tex[t]-Mex: Seductive Hallucination of the "Mexican" in

America. In August 2009, Nericcio began his new post as Director of the Master of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. A companion piece to this essay sobre Laredo appears in SDSU PRESS's Border Lives (1995); a selection appears here. |

A

Final After Frame

A

Final After Frame