| Last updated 6, AUGUST 2015 |

|

| Cinematography, Photography and Literature An Introduction to Pull My Daisy--A Triptych by Robert Frank © 2000, 2015 William Anthony Nericcio |

It

is

an unknowable odyssey that characterizes our movement

into the world of life and consciousness. We are

born--torn from the comfort of a warm, dark and

profound penumbra and thrust into the sharp shock and

pandemonium of a brightly lit operating room, our eyes

take on a life of their own, and what they communicate

to us and how they communicate to us over the years

begins to shape the contours of what we call our

psyche, when we are talkin’ prettyfancy, and merely

our self when we spend those silent sacred

moments each morning before the mirror wondering who,

or, what that thing is, that sentient organism with

the curious eyes, looking back at us from the

reflecting glass. It

is

an unknowable odyssey that characterizes our movement

into the world of life and consciousness. We are

born--torn from the comfort of a warm, dark and

profound penumbra and thrust into the sharp shock and

pandemonium of a brightly lit operating room, our eyes

take on a life of their own, and what they communicate

to us and how they communicate to us over the years

begins to shape the contours of what we call our

psyche, when we are talkin’ prettyfancy, and merely

our self when we spend those silent sacred

moments each morning before the mirror wondering who,

or, what that thing is, that sentient organism with

the curious eyes, looking back at us from the

reflecting glass.

The pandemonium of this remarkable light--the cacophony of its lucid intrigues is what our photographers help us to adjust to in the worlds of their remarkable art. We turn to photography to adjust to the light, to remind our eyes or retrain our vision so that just maybe we will actually see what transpires in front of our eyes. The old truism about blindness and insight isn't very far off the mark and it is a very amazing and rare thing when we actually can see the forest and the trees.

The next panel of the triptych is film, and lastly we have Literature. With Robert Frank's work we are asked to confront all three. Noted for his association with Beat Writers in our Post-World War II American literary renaissance, Frank's photography comes to fame as a result of a Guggenheim sponored journey across the United States by car in the early 1950s with camera in hand and small family in tow. Walking slowly through the exhibit rooms in this exquisitely designed museum, one is made aware of the ironic density of Frank's work, and the ironic profundity of the United States, a nation we intelligentsia are used to critiquing, but never quite actually fathom--Frank's alien eye, su ojo estranjero, aided by its prothesis, the camera captures a diverse, sometimes decadent, United States of America, a country obsessed with automobiles, beauty spectacles and itself. A close look at the images reveals a Robert Frank who is obsessed with the idea of America--American flags, American movies, American presidents, parades, children, cowboys and ministers. Which brings us to the second idea pulsing through the veins of the exhibit, and that is the domain of the sacred, of the spiritual, of that quest to find or make Gods in this always transient world. Kerouac writes in the film we are about to see that the Beat poets diaries are portals in which "their sacred naked doodlings do show" and at once the mirror on the wall reveals itself to be the material doppelganger of these innovative poet’s journals, both oddly sacred altars for the worship of the self.

Here’s a taste: The humor, the

sadness, the EVERYTHING-ness of these pictures! ...

--Long shot of night road arrowing forlorn into

immensities and flat of impossible-to-believe

America in New Mexico under the prisoner’s

moon--under the whang guitar star...

Hoboken in the winter, platform full

of politicians all ordinary looking till suddenly at

the far end to the right you see one of them pursing

his lips in prayer politico (yawning probably) not a

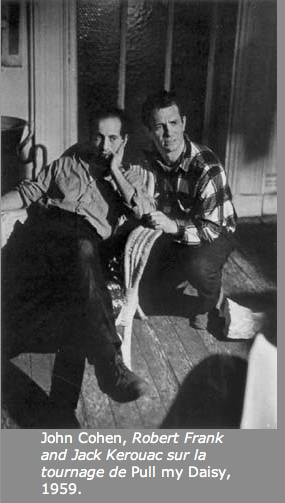

soul cares." The New York Institute for Photography Photographer's Spotlight on Robert Frank reveals that, "While he was assembling his ground-breaking book, Robert Frank ran into his Beat generation buddy, writer Jack Kerouac, at a party and showed him his photos. Kerouac was very impressed and was promptly commissioned to write the introduction for The Americans. Frank traveled cross-country in 1955-1956 shooting over 28,000 images, 83 of which were selected for his book. Going against the tide of perfectly focused and lit images, Frank's photos are grainy, sometimes blurred. Frank became a fly on the wall and photographed people in the most private and public places" Frank and Kerouac, Swiss lensman and American wordsmith together once again here on this page with you and me.

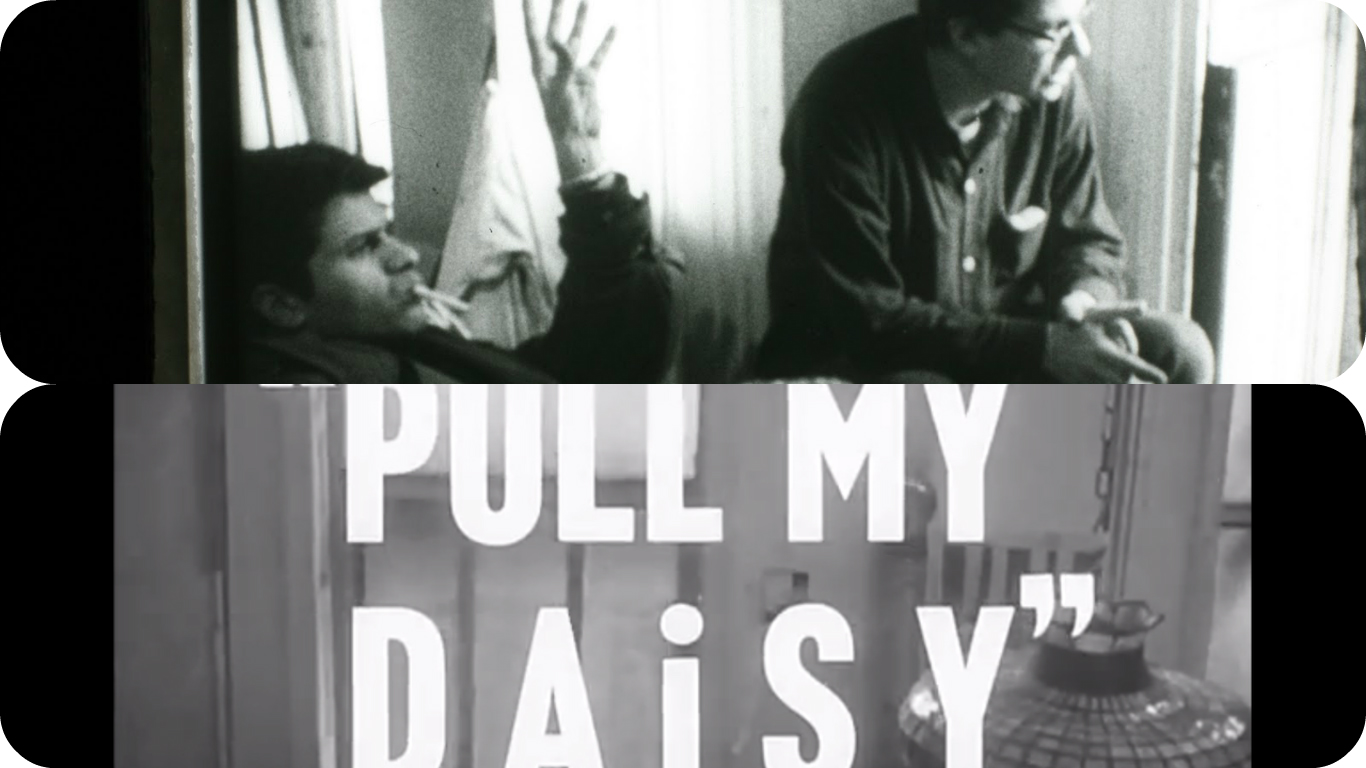

Ray Carney’s critical overview succinctly documents the work that went into the production: "Pull My Daisy was praised for years as a masterwork of free-form "blowing" before Alfred Leslie revealed in a November 28, 1968 Village Voice article that its scenes were as completely scripted, blocked, and rehearsed as those in a Hitchcock movie. The film was shot on a professionally lit and dressed set. The cast worked from a script, and shooting proceeded at the typical studio snail's pace of two minutes of text per day. All camera positions were locked and all movements planned in advance. As many takes and angles were shot, and as much footage exposed (30 hours) as for a Hollywood feature of the period. Probably more. Even Kerouac's wonderfully shaggy-baggy narration was actually written out in advance, performed four times, and mixed from three separate takes. (Though, in defense of the man who made "first thought, best thought" a Beat mantra, it must be added that he is said to have objected when his narration was edited.)"

So what are we about to watch; I want to do as much of my commentary as we can before we watch the film, so that we can plunge into a discussion after the lights come up. So here are some key things to watch for or questions to think about as we screen the movie. What is the connection between Robert Frank’s work as a photographer and his work as a cinematographer and film-maker? Although Alfred Leslie directed Pull my Daisy, it was Frank’s lens and Frank’s eye that pulled the focus and framed the scenes, so this gives us a great oppportunity to watch a gifted artists working across two technologies.

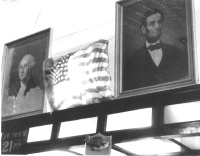

Other things to think about: In 1957, Robert Frank’s mentor, Walker Evans, had written that Frank’s photography was a "far cry from all the wooly, successful ‘photo-sentiments’ about human familyhood," and that what was its value was its "irony and detachment." It is without question that Frank’s is a master of irony we can see this in his immortalization of Washington and Lincoln in a Detroit bar,

his juxtaposition of Political Campaign posters with a billiards table, exposing the endless routine of strategy and power intrinsic to both, the South Carolina television that goes on and on without an audience to take in its ubiquitous monotony....

But do these representational

tactics, this optics of irony, play as well in his

cinematography? And a further

Let us now move to our silver screen with the San Diego Museum of Photographic Arts premiere screening of Robert Frank, Alfred Leslie and Jack Kerouac’s 1959 opus, Pull My Daisy. As with Buńuel and Dali's

surrealistic classic Un Chien Andalou

(1929), cinematographer Frank, writer Kerouac,

director, Alfred Leslie and crew play it fast and

loose with reality in this bizarre tale of

fastdrinking, fast-talking BEATpoets, their annoyed,

un-named women, and a rather peculiar preacher named

"Bishop."

|

| nota bene: Unedited

Reading Script from a Public Lecture @MoPA, San Diego,

October 5, 2000--QUOTE AT YOUR OWN RISK! The images that appear in this essay are the property of the original copyright holders and are not for reproduction without the direct authorization of those individuals. Here, the Internet is at one with our biological domain--in short, reproduce at your own risk. On 6, September 2008; I was asked to remove the images reproduced here by attorneys for Robert Frank's estate; I have asked them to leave the essay intact citing fair-use copyright laws. |

When Neal arrived home from

work, he took the part of his wild-man buddies over

that of his wife and her clergyman. In 1959,

Kerouac, Ginsberg, and some Greenwich Village

friends hatched a plan to make a short film, using

the third act of Kerouac's play, which dramatized

the bishop's visit, as the central event. They

wanted to call it "The Beat Generation". However, it

was discovered that MGM had copyrighted the title,

and were about to give it to a B-movie featuring a

rapist on the run from the police. When not

terrorizing women, the villainous hero of the film

The Beat Generation hangs out in espresso bars and

at beatnik parties, where strange dances are

performed by men with goatee beards and dyed-blonde

beat-chicks to the rhythm of the bongo drums--[allow

me to interject here that one of the more

interesting aspect in watching this film is to see

how Kerouac, Ginsberg and Orlovsky are already

reacting against the popularity and celebrity of

Beat, commonly misnamed Beatnik Culture]. Campbell

continues: "The alternative film went ahead. It was

called Pull My Daisy, a title borrowed from the

early poem by Ginsberg which had appeared in the

magazine Neurotica. The director was the Swiss

photographer Robert Frank. Ginsberg, Orlovsky and

Corso were given parts, the former pair to play

themselves, and Corso to move between himself and

Kerouac...the technique and spirit of the film were

improvisatory; it was a jazz movie, a boy-gang

reunion, a homage to the still imprisoned Neal

Cassady, and a jeer at his wife....All the essential

elements of the boy-gang are there:

anti-authoritarianism, jazz, bop-prose narration,

girls-in-dresses-better-left-at-home spilling into

misogyny, boys' adventure spilling into

homosexuality. It is the emblematic Beat Generation

film." The irony of all this is that though Kerouac

wrote the screenplay and provides the narration he

was barred from the set by Director Alfred Leslie,

for, as Barry Miles puts it in King of the Beats

"arriv[ing] inebriated expecting to party,

accompanied by a particularly smelly, drunken bum he

had found in the gutter in the Bowery [of New York

City].

When Neal arrived home from

work, he took the part of his wild-man buddies over

that of his wife and her clergyman. In 1959,

Kerouac, Ginsberg, and some Greenwich Village

friends hatched a plan to make a short film, using

the third act of Kerouac's play, which dramatized

the bishop's visit, as the central event. They

wanted to call it "The Beat Generation". However, it

was discovered that MGM had copyrighted the title,

and were about to give it to a B-movie featuring a

rapist on the run from the police. When not

terrorizing women, the villainous hero of the film

The Beat Generation hangs out in espresso bars and

at beatnik parties, where strange dances are

performed by men with goatee beards and dyed-blonde

beat-chicks to the rhythm of the bongo drums--[allow

me to interject here that one of the more

interesting aspect in watching this film is to see

how Kerouac, Ginsberg and Orlovsky are already

reacting against the popularity and celebrity of

Beat, commonly misnamed Beatnik Culture]. Campbell

continues: "The alternative film went ahead. It was

called Pull My Daisy, a title borrowed from the

early poem by Ginsberg which had appeared in the

magazine Neurotica. The director was the Swiss

photographer Robert Frank. Ginsberg, Orlovsky and

Corso were given parts, the former pair to play

themselves, and Corso to move between himself and

Kerouac...the technique and spirit of the film were

improvisatory; it was a jazz movie, a boy-gang

reunion, a homage to the still imprisoned Neal

Cassady, and a jeer at his wife....All the essential

elements of the boy-gang are there:

anti-authoritarianism, jazz, bop-prose narration,

girls-in-dresses-better-left-at-home spilling into

misogyny, boys' adventure spilling into

homosexuality. It is the emblematic Beat Generation

film." The irony of all this is that though Kerouac

wrote the screenplay and provides the narration he

was barred from the set by Director Alfred Leslie,

for, as Barry Miles puts it in King of the Beats

"arriv[ing] inebriated expecting to party,

accompanied by a particularly smelly, drunken bum he

had found in the gutter in the Bowery [of New York

City].

complication

to

complete the triptych, are these ironies to be found

as well in the Beat literature and poetry that

Franks body of work spans? I think the answer to

this long question is yes, and I’ll just give you a

peek at a quick example: in the midst of a soliloquy

on the nature of what is holy, Frank, here both

cinematographer and film editor, gives us a snapshot

of an alka seltzer container, anticipating Andy

Warhol in his expose on the sanctity of commercial

culture for Americans, and revealing I think as

well, that the Beats drank a lot and probably needed

the stuff every morning.

complication

to

complete the triptych, are these ironies to be found

as well in the Beat literature and poetry that

Franks body of work spans? I think the answer to

this long question is yes, and I’ll just give you a

peek at a quick example: in the midst of a soliloquy

on the nature of what is holy, Frank, here both

cinematographer and film editor, gives us a snapshot

of an alka seltzer container, anticipating Andy

Warhol in his expose on the sanctity of commercial

culture for Americans, and revealing I think as

well, that the Beats drank a lot and probably needed

the stuff every morning.  The most complex mirror sequence of the film comes

when we hear Kerouac say, "Cockroach of the eyes,

mirror, boom, bang, dream, Freud, Jung" and at some

deep level the concerns for representation central

to Kerouac and to Frank converge in word and image

on the screen.

The most complex mirror sequence of the film comes

when we hear Kerouac say, "Cockroach of the eyes,

mirror, boom, bang, dream, Freud, Jung" and at some

deep level the concerns for representation central

to Kerouac and to Frank converge in word and image

on the screen.